Back in February 2022, when Russia invaded Ukraine, we wrote an article called The End of the Peace Dividend – making the argument that the long and valuable period of peace (and the very low levels of spending on defence) that the West had enjoyed for decades following the end of the Cold War was over. At the time, it caused a bit of a stir and some observers were critical of our stance – they made the case that there was simply no need or logical reason for Russia to attack its neighbour, Putin would be brought to heel one way or another and in any case he needed to sell Russian gas and oil to Europe to keep Russia’s economy afloat – so why would he upset such an important customer and put Russia’s economy at risk? If Putin proved recalcitrant, the combined efforts of the US, EU, UK (and potentially NATO, if he decided to attack a NATO member such as Poland) would bring the situation under control. In short, there was nothing for us (or anyone else) to worry about. In a global and interdependent economy, it always pays for everyone to collaborate – or so the logic went.

Wind the clock forward nearly two years and Russia is still at war with Ukraine with no end in sight. On top of that, there is now a very serious conflict in the Middle East which has already morphed into a regional ‘proxy’ war. At the moment, it is not clear to us how any of these conflicts will be resolved. This matters, because the supply chain disruption that became one of the characteristics of the Covid pandemic has started to re-emerge once again. Indeed, central bankers are talking about the risk of supply chain disruptions on the economic outlook, which naturally has significant consequences for monetary policy.

A container load of trouble

For the last two months, cargo ships and civilian ships in the Red Sea have been subject to a barrage of drone strikes, missile strikes and hijackings – there have been so many attacks that more than 500 container ships have chosen to change their route and take the much (40%) longer (and hence more expensive) route around the Cape of Good Hope, rather than travelling the much shorter route to Europe via the Red Sea and the Suez Canal.

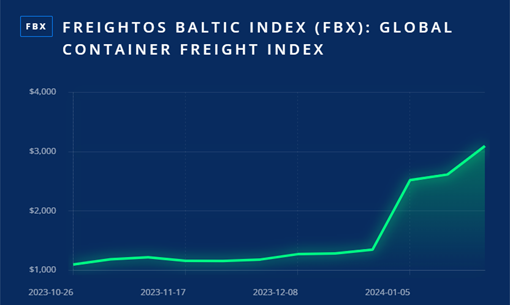

At the moment, Bloomberg suggests that around a quarter of the world’s container ship capacity is on diversion. The impact on the price of moving goods around the world has been predictable but profound: the Freightos Baltic Global Container Freight Index (FBX), a proxy for global shipping container rates for 40-foot containers, has gone up more than three times since October:

Source: Freightos, January 2024. Price for a 40ft standard shipping container.

Of course, it is not just rising shipping costs that cause problems for importers and exporters. Inventory is stuck at sea for longer, which means disruption to production schedules and delays for customers. When the containers do eventually arrive at port, they arrive later than expected, perhaps significantly so, which means further disruption and a potential shortage of containers. Anecdotally, we have heard that companies making shipping containers are having to work flat out to meet demand. Air freight is an (expensive) alternative for companies who need to send small and high-value goods, but for bulky things like commodities, construction materials and large consumer durable items like cars and auto parts, it is neither practical nor affordable when compared to cargo or container ships.

Companies with complex global supply chains are therefore stuck between a rock and a hard place. Maersk, one of the most important shipping companies in the world, expects the disruption to last for several months at least. If you want to send goods by the safer (longer) route, you have to wait – according to Bloomberg, container ships travelling via the safe Cape of Good Hope route are already fully booked until the summer at least.

What are the economic impacts?

Prosaically, higher container rates + merchant sailors asking for danger money + higher insurance costs = higher prices. That part of the equation is relatively simple. Whilst it traded in a relatively narrow range in Q4, Brent crude oil prices have been climbing steadily since the turn of the year, reflecting geopolitical risks, and WTI (West Texas Intermediate) has been on a similar path, albeit the USD/bbl spread between Brent and WTI remains relatively wide by recent historic standards. Is the oil market complacent? Perhaps a little, but in our mind the wide possible range or ‘fan’ of outcomes for oil prices is so wide that it has to be worth considering mitigating the risk that oil prices continue to rise due to the worsening geopolitical backdrop.

We also wonder what might happen if the Houthis were to (accidentally or deliberately) sink a ship carrying oil. One positive here is that the very large oil tankers heading from the Middle East to the US already travel via the Cape of Good Hope, as their huge displacement when fully loaded means that they can’t travel via the Red Sea and the shallow and narrow Suez Canal. That might be one reason why oil prices haven’t spiked. Nonetheless, as things stand today, economists at JPM reckon that if the spike in shipping costs persists, it could add 0.7 percentage points to global inflation in the first half of 2024.

One source of comfort for investors, at least in terms of the potential inflation impact, is that supply chain disruption is nothing new; in the pandemic companies were forced to adapt, and trends such as ‘onshoring’ and ‘re-shoring’ have clearly accelerated since then. However, experts in global logistics have said that three years is simply not long enough to disentangle complex global supply chains without causing some delays or difficulties.

In the UK, the economic impact of the conflict in the Red Sea is already showing up in the soft economic data: S&P’s Composite PMI (Purchasing Manager’s Index) has showed that suppliers’ delivery times lengthened for the first time for 12 months in January following the Houthi attacks. Capital Economics have described UK pricing pressures as ‘sticky’, and noted that the recent data points will add to investors’ unease about the potential persistence of inflation. S&P noted that longer journey times are lifting factory costs “at a time of still-elevated price pressures in the service sector.” S&P also warned that UK inflation may “remain stubbornly higher in the 3% to 4% range” in the near future. It is worth remembering that while global supply chains had improved prior to the Houthi attacks, they were not operating at normal pre-pandemic levels across all sectors and industries.

The Houthis have said very clearly that the attacks on shipping in the Red Sea will continue for as long as Israel continues to attack and blockade Gaza. Clearly, Israel’s PM Netanyahu is coming under increasing pressure to de-escalate the war, but it is not clear to us how or when that could happen, not least because Israel rejects a two-state solution, which is what most Western powers demand. Concerted Western pressure on Israel to stop the attacks on Palestine has had no impact so far and conservative estimates suggest that over 25,000 Palestinians – easily more than 1% of the population and reportedly mainly women and children – have been killed in Israeli attacks. Meanwhile, the US and UK have targeted the Houthis via air strikes, with the aim of destroying their stockpiles of arms of drones. Given that the Houthis are reportedly well supported and supplied by Iran, this could become a prolonged regional intervention. As one US National Security Adviser said recently, deterrence is not simply a light switch that you can turn on and off.

Conclusion

It is worth bearing in mind that bond markets, and indeed all financial markets, are predicated on the idea of rational behaviour – indeed, some academic theses suggest that financial markets are so perfectly rational that it is almost impossible for active investors to make money from investing in them, once trading costs are taken into account.

The past few months, and indeed recent years, have shown us that human behaviour is anything but rational, and has potentially become more irrational of late. It is not rational to bomb your immediate neighbour day after day and then assume that the situation could go back to normal the day after the conflict stops. Similarly, it is not rational to fire missiles or armed drones at large, slow-moving container ships which may be filled with chemicals, plastics or other goods that might cause a huge environmental catastrophe – on your own doorstep – if the ship sinks, as well as potentially killing or injuring the crew, but people are doing just that on a daily basis because they have other objectives. The Houthis may say they don’t deliberately target oil tankers in the Red Sea (although recent evidence would seem to contradict that) but what would happen to the global energy complex if a tanker was sunk?

Looking at it another way, there are plenty of what could be labelled ‘bad actors’ out there – and the truth is that the more disruption they cause, the better it is for them, as that gives them more leverage locally and internationally. At the moment, assuming that all economic and political actors will display rational economic behaviour economic is flawed, as the world is fragmenting and old, long-established assumptions and conventions have started to dissolve. We often hear of the ‘Global North’ and the ‘Global South’, but we fear that the divisions – both politically and economically – are probably much wider and deeper than that.

As bond investors, we lend our capital to companies, they return our capital (the ‘principal’) at a known date in the future, and we are paid to wait in the interim through regular coupon payments. We do this because we need to generate returns for our investors and the company needs money to invest in its business and (hopefully) prosper – everyone wins. That very simple model of mutually beneficial cooperation over a long period of time is a very long way away from what is going on in many parts of the world at moment.

We’ve long argued that inflation would be sticky on the way up (once people start getting used to higher prices they demand higher wages, which push prices up, and then the cycle begins again because higher wages = higher prices). Now it is becoming clear that, because of supply chain disruption, inflation could be sticky on the way back down. Given the geopolitical backdrop, one cannot assume that inflation simply falls away in 2024. In the UK, the recent data releases are consistent with ‘stagflation’ – little or no GDP growth (i.e. stagnation) combined with inflation. In the US the economic picture looks better but supply chain disruption is real. And in Europe, Madame Lagarde has said that she is watching supply chain disruption, which means that it will be a factor in the European Central Bank’s policy decisions.

In Q4 2023, both equity and bonds rallied strongly on the hope of an ‘immaculate disinflation’ scenario in 2024. If recent events and data releases are any guide, that hope now looks a little misplaced. In the US, 10-year breakeven inflation rates remain modest at just 2.3% according to the St. Louis Fed; this means that the market’s best estimate is that US inflation will, on average, be 2.3% per year over the next 10 years. Given the geopolitical backdrop, and the ongoing disruption to supply chains as discussed above, we think there might be some upside risks to that assumption (there could be positive gains). If US inflation does turn out to be more than 2.3%, inflation-linked bonds will outperform conventional bonds. And remember that inflation-linked bonds are a ‘heads you win, tails you don’t lose’ asset class – if inflation does ease for whatever reason, that implies some potential central bank rate cutting, which is positive for global inflation-linked bonds as like equities they are a long duration asset class, and that duration sensitivity means they will benefit from falling ‘risk free’ interest rates.

As well as providing a useful and highly liquid inflation hedge, skilled global inflation linked active managers can add value to client portfolios through country and duration positioning, and by making strategic and tactical allocations to corporate inflation issues in markets like the UK. The latter can provide much better all-in yields than a government issue with materially less duration risk. Additionally, the continuing growth of passives and ETFs means we can exploit relative value opportunities in very good-quality bonds which passives and ETFs have been forced to sell or liquidate simply because the bonds have dropped out of the major indices (say because their maturities are less than one year). A recent example was a January 2025 bond which fell out the index and which we were able to pick up with a c.3% real yield, and an undemanding breakeven at 1.94%.

Past Performance is not a guide to future performance and may not be repeated.

Important information

This communication is marketing material for professional investors only. The opinions are those of the named author(s) at the time of publication and are subject to change, without notice, at any time due to changes in market or economic conditions. Whilst care has been taken in compiling the content of this document, neither Sanlam nor any other person makes any guarantee, representation or warranty, express or implied as to its accuracy, completeness or fairness of the information and opinions contained in this document, which has been prepared in good faith, and to the fullest extent permissible under UK law.

This document is provided to give an indication of the investment and does not constitute an offer/invitation to sell or buy any securities in any fund managed by us nor a solicitation to purchase securities in any company or investment product. It does not form part of any contract for the sale or purchase of any investment. The information contained in this document is for guidance only and does not constitute financial advice.

Past Performance is not a guide to future performance. The value of investments and the income from them may go down as well as up and investors may not get back the amounts originally invested.

Any sectors, securities, regions or countries shown above are for illustrative purposes only and are not to be considered a recommendation to buy or sell.

The forecasts included should not be relied upon, are not guaranteed and are provided only as at the date of issue. Our forecasts are based on our own assumptions which may change. Forecasts and assumptions may be affected by external economic or other factors.

Issued and approved by Sanlam Investments which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Sanlam Investments is the trading name for Sanlam Investments UK Limited (FRN 459237), having its registered office at 24 Monument Street, London, EC3R 8AJ.